North Carolina State University Athletics

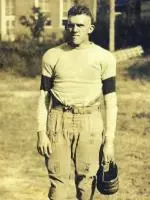

PEELER: The First Football All-American

8/11/2008 12:00:00 AM | Football

It may not have been a fluke, exactly, but there was definitely a hint that he may have received a bit of kindness from legendary football figure Walter Camp during perhaps the most trying time in the history of NC State football.

Still, Ripple is memorialized at Carter-Finley Stadium and in NC State's record books as one of many who have earned national recognition for their outstanding accomplishments on the gridiron for being named to Camp's second-team All-America squad in 1918.

Now, more than 110 years after he was born on the bad side of town in Lexington, N.C., and nearly four-and-a half decades after he was buried in Spray, N.C., Ripple's legacy has been renewed, with vigor, thanks to a scholarship endowed by the late tackle's family.

Ripple's wife, Ann Reynolds Ripple, died on March 10, 2007, six weeks shy of her 100th birthday. She had lived off her husband's investments since 1965, a nest egg that grew exponentially in recent years because of a well-managed stock portfolio that John Ripple put together because old football injuries prevented him from getting life insurance. The stocks were modest when Ripple died, but they grew with dividends at such a rate that, at the time of her death, Mrs. Ripple was a wealthy woman.

In March, Ripple's daughter, Joan Ripple Clark, settled her mother's estate. Soon after, she delivered a $100,000 check to Wolfpack Club Executive Director Bobby Purcell and Associate Executive Director Buzzy Correll, to permanently endow a football scholarship for an offensive lineman in honor of her parents.

"We couldn't think of a better way to memorialize my parents than by setting up a scholarship at NC State," said the 76-year-old Clark, who lives in Fearrington Village near Pittsboro.

Purcell gratefully received the gift, of course, but was almost as enthralled by the stories he heard during a two-hour visit with Clark, which included anecdotes about the earliest days of NC State football.

"Her stories were so much fun to listen to," Purcell said. "They go all the way back to the roots of our university and our football program. This scholarship will not only ensure that we remember that part of our history, but it will also ensure that student-athletes will help our football program for years to come.

"The Ripple family means a lot to the university and our athletics tradition."

Until you hear the stories, you don't really know how much.

A football star

John Hollis 'Gus' Ripple (b. Oct. 25, 1897-d. July 27, 1965) arrived at the newly named North Carolina College of Agriculture and Engineering in the fall of 1917 from Lexington, the oldest son of a single mother. He was the first person from his part of town to earn a high school diploma, not to mention go to college. He paved the way for his younger brother to join him in Raleigh four years later.

Ripple came from modest means, but he excelled as an athlete, particularly on the basketball court. He had never played football before arriving at NC State, but he joined Harry Hartsell's gridiron team because he believed it would be his gateway into college athletics.

The Agromeck called the inexperienced freshman 'the find of the season'. He developed into one of the most dependable players on the team and a tower of strength to the center of the line. He definitely had an advantage: at 6-2, 200 pounds, he was one of the biggest players on the squad.

Still, he played sparingly on a team that finished with a 6-2-1 record and claimed the North Carolina state championship.

The fall of 1918 was a trying time worldwide, across the nation and on the NC State campus. 'The Great War' was raging in Europe and all 590 regularly enrolled students were enlisted in the Student Army Training Corps, in an effort to populate the various branches of military with trained officers. The school had five infantry battalions and one naval unit, turning the entire campus into a military college, with regimented drills conducted every morning and military science classes held throughout the week.

Earlier in the year, a Spanish influenza outbreak started in the Rocky Mountains and quickly spread around the globe, creating a pandemic that was worse than the outbreak of bubonic plague in medieval Europe. For the next two years, the virulent flu bug killed more people than died throughout the course of World War I. More than 675,000 people in the United States alone died of the flu, 10 times the number of American military that died in the trenches across Germany and France.

Ripple, a Boatswain Mate First Class in NC State's Company F (Naval Unit), was affected by the bug. He enlisted in the Navy in the summer of 1918, but caught the flu and was quickly discharged. He returned to school in time for the team's 54-0 season-opening victory over Guilford.

By then, the flu had arrived at NC State, killing 13 students and two nurses at the college infirmary. (One of the nurses was the daughter of school president W.C. Riddick, for whom Riddick Stadium was named.) In all, some 450 students, faculty and staff were infected by the outbreak.

For five weeks, all extra-curricular activities, including football practices and games, were cancelled. In addition, more than 30 students who had not been affected by the flu bug were shipped out to Army camps across the country as officers, including seven regulars from the '17 football champions.

After taking off all of October and the first weekend of November, first-year coach Tal Stafford's team received permission to resume practice a week before the team was scheduled to face national power Georgia Tech in Atlanta.

Tech coach John Heisman had led the Golden Hurricane, as his football team was then known, to the 1917 national championship with a perfect 9-0 record. Two years before, the Hurricane recorded a 222-0 victory over Cumberland College, the most lopsided game in the history of college football. (Neither team in that game made a first down Cumberland because it never got more than 10 yards away from its original line of scrimmage and Georgia Tech because it never needed more than four downs to score against its hapless opponent.)

Heisman's 1918 squad was better than the previous two, even though it lost to Pittsburgh 32-0 two weeks after playing NC State.

With a team that was weakened by the flu and decimated by military call-ups, the Farmers had little chance against Heisman's powerful crew. Four NC State players were hurt on the opening kickoff. The Hurricane scored two touchdowns in the game's first four plays. The score was 33-0 at the end of the first quarter, and Heisman sent in his second string for the second quarter. They pushed the halftime score to 75-0.

State's only highlight came in the third quarter, when Ripple recovered a teammate's fumble and returned the ball 75 yards for a touchdown. However, the play was called back because the Farmers were whistled for being off-sides.

Ripple and his teammates long believed there were reasons besides attrition that they never stood a chance against Heisman's team. Three times -- according to Tom Park, a freshman on the varsity that season -- Georgia Tech's kicker sailed the ball into the stands behind the end zone, only to have the fans throw the ball back onto the field so their team could recover three 'fumbles' in the end zone for touchdowns.

Four minutes into the final quarter, State captain W.D. Wagner requested that the game end, with the Georgia Tech leading 128-0.

"From that day on, Daddy said he wouldn't play games in Atlanta because you could never get a fair shake there," Clark remembers.

But, it just so happened that legendary sports writer and football coach Walter Camp, who promoted college football with the most prominent annual list of All-America players, was in the stands for the contest between NC State and Georgia Tech and was greatly impressed with Ripple's abilities.

The Farmers went on to lose its final two games, 25-0 to Virginia Tech and 21-0 to Wake Forest, meaning Stafford's team had been outscored 174-0 in its final three games. But at the end of the trying season, Camp named Ripple second-team All-America, perhaps for what he did on that single disqualified play in a blowout of historic proportions.

Still, Ripple became the first football player from a North Carolina college to be recognized as one of the best players in the nation.

Ripple played two more seasons, both under Bill Fetzer, who became NC State's fifth coach in five years in 1919. State won a school-record seven games in both '19 and '20, with the husky Ripple a key component for an offense that scored at least 78 points on five occasions.

A basketball standout with a temper

Ripple always considered himself better at basketball than football, and the Farmers were pretty good during a time when there were no postseason tournaments to look forward to. The goal was to win state championships, and teams had to agree to face each other in end-of-season playoffs.

NC A&M won the 1918 and '19 state titles, and had a chance to win it again in 1920. But a last-second shot from midcourt by a substitute allowed Trinity College (now Duke University) to win the state title.

Ripple was elected captain of the basketball team for the 1920-21, but was suspended from the squad midway through the year because he questioned the judgment of a game official.

"Something happened, though he never really would say what," Clark said of her father's suspension. "He accused an official of being dishonest. My father was a very honest man, but he had the diplomacy of a bull in a china shop.

"So whatever happened, my father was not proud of. He didn't want to discuss it."

Ripple's replacement at captain, Robert Deal, also had to leave the team because of a finger injury. The Farmers fell to 4-13 in the regular season, including a bitter 62-10 loss to North Carolina in Chapel Hill and double-digit losses to Wake Forest and Duke.

At playoff time, however, Ripple was exonerated and returned to the team to help the Farmers avenge earlier losses by beating Wake Forest 20-10 and North Carolina 32-31. Ripple scored half of his team's points, including 14 in the first half, to set up a championship game rematch with Trinity. This time, however, the Blue Devils took an early lead and defeated A&M 34-24, ending Ripple's NC State athletic career.

"He always liked to talk about his basketball career," Clark says of her father. "He always said he was a better basketball player than football player. He just got more recognition in football."

Not a life in vain

Ripple graduated from NC State's School of Textiles in 1921, and immediately moved to Fieldale, Va., to begin work as a trainee for Marshall Field and Company. He became the manager of the towel mill in 1940. In 1949, he became the manager of Fieldcrest's Sheeting and Blanket mill in Draper, N.C., where he stayed until he retired in 1963.

He was an active church leader and Rotarian in the small communities where he lived most of his life. He was on the advisory board of the Fieldale branch of the First National Bank of Martinsville and Henry County, Va., and an active member of the American Legion.

"You see why I'm proud of him?" Clark says. "Not just because he was an All-America football player. Daddy left a modest estate, but mother was very, very comfortable. We always lived comfortably. But he took care of my mother, me and my family.

"I heard my father say many times if the only thing his obituary said was that he was an All-America football player, then the last 40 years of his life were in vain."

John Ripple died on July 27, 1965, at Duke Hospital in Durham after a six-month illness. He is buried at Overlook Cemetery in Spray, N.C.

His obituary mentioned his All-America football career. But not until the second paragraph, long after he was identified as a community leader and retired business executive.

"Hopefully, you have discovered that he was a good citizen and a good businessman," Clark said in a note she sent along with some newspaper clippings. "I know he was a good father."